Think of Christmas. Think of an artist. In the sweet spot where the two come together, the chances are that many of us will be thinking of Norman Rockwell artworks.

And no wonder. The spirit of the season was woven through his career like a length of tinsel. The pivotal drawing that convinced young Norman’s parents to allow him to attend art school at the age of 14 was of Scrooge, the central character in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. He painted his first commission of four Christmas cards before his sixteenth birthday. And during a career spanning over six decades he produced a string of Christmas-themed paintings and illustrations that, for many, are as evocative of the warmth, nostalgia and optimism of the festive season as robins and puddings.

Christmas made real

Part of the appeal is that, while many Rockwell paintings and prints capture an idealised, chocolate-box magic that sometimes seems too good to be true, the wry observations and tiny, human details reflect the realism of the season too—the noise and clutter, effort and exhaustion that we can all identify with, and which is so often necessary to make the magic happen.

Who doesn’t sympathise with the weary shop assistant in Tired Sales Girl on Christmas Eve?

As a commercial artist, Rockwell was steeped in the modern materialism of Christmas. Who doesn’t sympathise with the weary shop assistant in Tired Sales Girl on Christmas Eve, collapsed against the wall at the end of her busiest shift of the year? And yet the humour and warmth of the season are there in abundance. While the blank smiles of the dolls echo the dazed expression on the sales girl’s face, we can smile inside at the thought of all the children whose Christmases she helped to make in those last chaotic minutes.

Rockwell sketched the scene from life in the Marshall Field department store in Chicago, persuading a waitress from a nearby diner to pose as his central character. The finished piece appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on 27th December 1947.

Santa and the Christmas Post

In total, Rockwell published 323 covers for The Post over 47 years, and the Christmas covers in particular have become much-loved favourites. Many feature his iconic vision of Santa Claus, firmly establishing that jolly plumpness and red suit in Western imaginations young and old. Take Santa Consulting Globe, otherwise known as Santa’s Good Boys after the title of the book in his hand. Santa’s humanity is all too apparent: showing his age, he needs a magnifying glass to plan his long night of deliveries, but the look on his face says he’s going to enjoy every minute.

Perhaps even more poignant is Rockwell’s last Christmas Post cover. He painted The Discovery in 1956, and no words are needed to clarify that moment of realisation—the split-second transition from innocent belief to adult understanding as the young boy stands in front of an open drawer, Santa costume spilling out behind him and fake white beard clutched in his hand.

Master of emotion

This ability to capture—and elicit—emotion is a key characteristic of Norman Rockwell art. In Christmas Homecoming, the joy on the faces of family and friends is clear as they welcome back a young man after a long absence. Family and friends. Gathering together. Precious moments with people we love. Themes that are central to so many of Rockwell’s pieces. And central to Christmas too.

Rockwell understood that the simple joys of human connection and kindness resonate with us on a far deeper level than much of the superficial commercialism that has long accompanied the festive season. As an advertising illustrator, his work was incredibly successful, precisely because it appealed to these deeper emotions rather than the fleeting desire to acquire the latest must-have purchase. Merry Christmas, Grandma…We Came In Our New Plymouth! was painted in 1950 to advertise Plymouth Automobiles’ Sedan model, yet it doesn’t show the car. Instead, it shows what the car could do: bring joy to families by bringing them together. That’s what made the advert so powerful, and why the image still enthralls us three quarters of a century later.

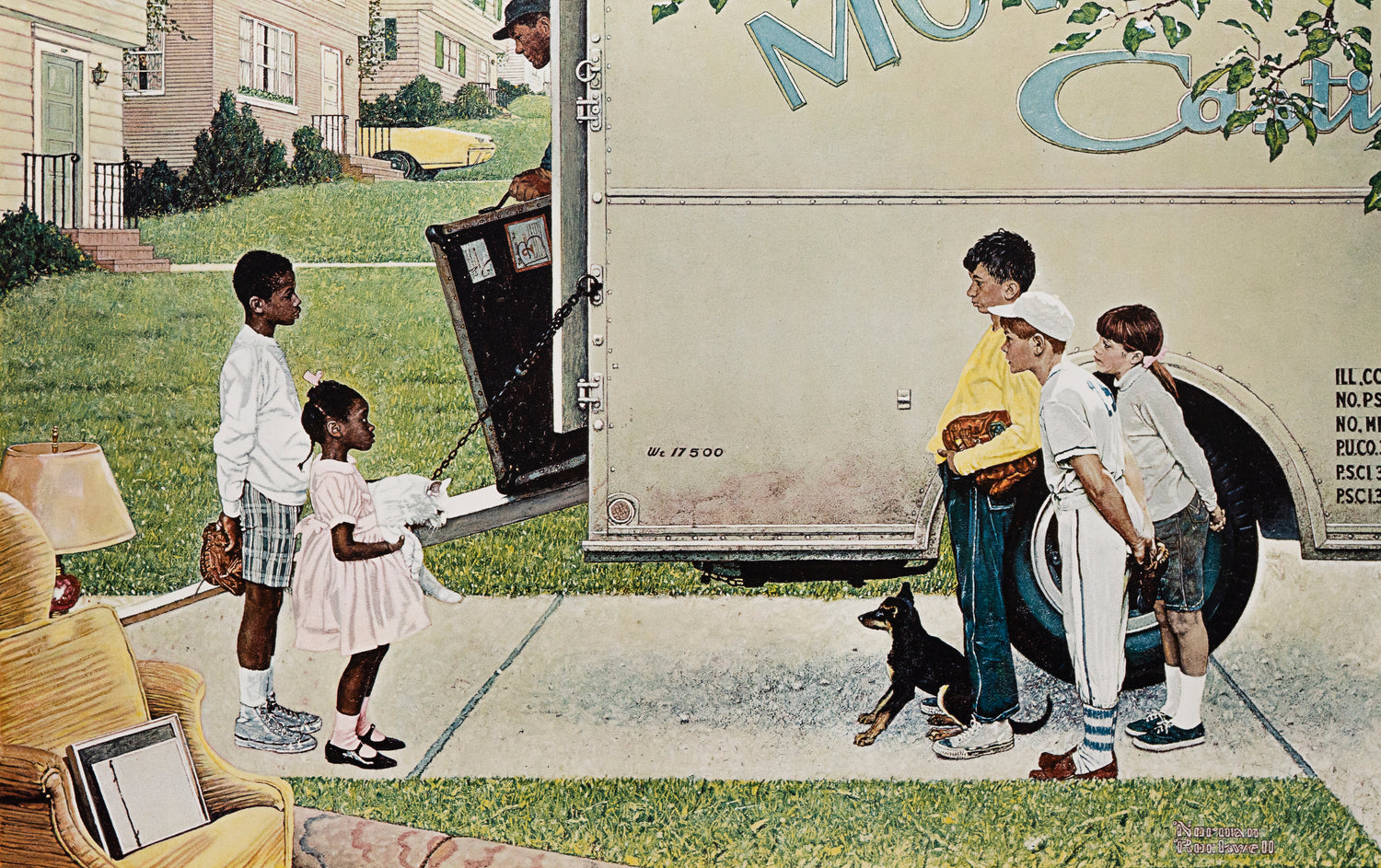

“I wish it could be Christmas every day”, sang Wizzard’s Roy Wood, and Rockwell certainly delivers on that score. These themes of kindness and connection, goodwill and community infuse his works far beyond the seasonal covers and marketing imagery. They shine out in his social commentary pieces such as Moving Day—a visual message of hope and new beginnings, friendship and unity. And the gentle humour of Barber Shop Quartet, with its four subjects united in song, reminds us that time spent with others, or even just thinking of others, whether it’s being someone’s Santa Claus or sharing a moment of silliness in the middle of a haircut, is always time well spent.

Explore our Signature Collection of artwork by Norman Rockwell or read more about Rockwell’s life and legacy here.